Salem Community College - Contributing to the International Glass Community

Salem Community College

Contributing to the International Glass Community

Honeybee Swarm with Flowers and Fruit, D. 6.0 inches, 2012; Chicago Art Institute

As a 14-year-old, in the mid-50s, I crafted a duck boat to paddle on the pond and glide on shallow water in the swamp near my home in rural Massachusetts.

My father, an introverted and detail-oriented chemist with an analytical mind, was impressed.

"Paul," he said, "your boat is well-crafted, you’re taking after your two grandfathers, both master craftspeople. I'm proud of you."

My Dad's praise for my hand skills filled me with pride. Over the next couple of summers, I loved paddling the duck boat on the pond and through its tributaries near my home, waterways that opened into shallow streams through swamps, places where I could experience the subtle hum of nature.

I didn't know it at the time, but all this would have a profound impact on my life.

I had never been able to impress my father with academic accomplishments, but I loved working with my hands and came to value his appreciation for my hand skills. I had done poorly in school; letters and words were confusing, sort of a scrambled code in my vision because of a disorder that most people had never heard of at the time – dyslexia.

Learning the Scientific Glassblowing Trade

My family moved to southern New Jersey, where I attended Pitman high school, still struggling with my studies. As a senior in high school, I picked up a brochure at the guidance counselor's office. Over dinner, I showed my father the brochure; it was from Salem County Vocational-Technical Institute. I wanted to do something with my hands and thought Salem's machinist program could be a good place to start. My father, a degreed bench chemist, looked over the brochure and noticed that one of the offerings was a program in scientific glassblowing.

"Paul," he said, pointing to the picture in the brochure, "this would be a good trade for you to learn. Glassblowers are very much in demand in the chemical world."

My father was actually excited, which startled me. He drove me to Salem City, where Salem Technical Institute, which opened in 1958, was housed in the second floor of a modest building that was once a hospital. We talked to the admissions person, who took us to the glass lab.

I was mesmerized when I saw eight to ten young men working at bench torches, in a variety of stages melting glass. Some were bending the glass tubing by softening it in a bushy, vibrant yellow-orange flame, while others were heating the tubing and pulling the end to a long point. This was over a half-century ago, but that image is still vivid in my mind. It was a combination of beauty from the flame, the drama of the hands working close to the flame, and the results of the individual effort that so intrigued me.

I enrolled the following September and proudly graduated in the class of 1963. I didn't fully understand it at the time, but I was entering a continuum of glass making going back centuries with the memory evidenced in the South Jersey glass tradition. I was entering an esoteric craft field that was taking advantage of 20th-century developments in glass, primarily borosilicate glass, which was designed to be heat- resistant and suitable for the scientific glass apparatus that was key to the expanding laboratory research and product development that followed World War II.

In fact, most of our Western knowledge has been unlocked as a result of experiments using glass apparatus.

Glass Career Evolves

During this period, I was committed to learning the scientific glass- blowing craft, but I was also equally interested in the South Jersey decorative art glass tradition – particularly, the beauty of the highly prized Millville Rose paperweight. The Millville Rose was a conceptual interpretation of a glass rose suspended in clear glass, often crafted by master furnace workers expressing their creative side at the end of the day. The Millville Rose was considered the crown jewel of the South Jersey glass tradition and a highly prized early 20th Century example of art glass on the decorative arts landscape.

Eventually, I would plant a foot in both the industrial and artistic worlds, first becoming a master in the scientific glassblowing craft. This led to working for a major chemical company. I was responsible for three glass shops in different research locations on different days in addition to working with bench chemists (like my dad) and scientists to custom- design and craft their glass apparatus requests. But, because of my need and drive to be on the creative side, after ten years of scientific glassblowing, I refocused my career to sculpt detailed floral designs based on the native flowers that had been my childhood fascination.

Now, looking back, I appreciate how the hand skills and technical foundation acquired at Salem Technical Institute gave me a distinctive advantage in my glass art making career.

Salem Community College’s Unique Role in Glass World

Today, glass education continues. The institute, renamed Salem Community College in 1972, has educated hundreds of enthusiastic students into professional glassmakers who have experienced a wide range of glass working processes. In fact, many students pursuing associate degrees in Scientific Glass Technology and Glass Art spend a third year taking additional glass courses to enhance their opportunities for self-employment.

Both disciplines are more than just an occupation. Many of the Art students continue towards a BFA degrees others work as studio artists/craftspeople. Scientific glass, for example, can be more than fabrication. It often involves working with scientists to help them visualize and design the equipment they work with to accomplish their experiments. Today, scientific glassblowers find lucrative employment in the South Jersey glass industry and university and corporate research laboratories around the country. The full range of laboratory apparatus crafted from catalog items to elaborate custom glass instruments are taught at the Glass Education Center at the college.

In a very real way, the students' skill will complement the service of science, impacting on the quality of life for all humanity.

Because of this unique program, which straddles art and science, Salem Community College students benefit from the interaction and exposure to all aspects of glass-working processes. They are part of a culture in which there is optimism about the future of glass, and their enthusiasm permeates the college.

One of the benefits of the school's yearly International Flameworking Conference, now in its nineteenth season, is well-known glass artists from around the world demonstrating and sharing technical and artistic insights with the glass students. Yearly, the conference averages three hundred attendees, giving glass professionals and students the opportunity to view technical displays featuring specialty colored glasses, tools, and glass-making equipment, and supplies from national manufacturers and distributors.

In the same way, the history of Silicon Valley led to a collective culture of creativity in technology, and the pockets of creative energy in and around the Penland School of Craft in North Carolina led to a fine craft culture, the same is happening in South Jersey. The glass tradition has informed the school's sixty years of teaching glassmaking. This collective knowledge has influenced a glassmaking synergy that nurtures excellence and innovation.

In many ways, Salem Community College's success is a story of the community’s collective vision, leadership, and gifted instructors. In1998 then-President Peter Contini invited me to lunch to discuss the glass program. This was my first official connection with my Alma Mater.

During lunch, we talked about the glass program and I was invited to attend an advisory board that was scheduled to meet the following week. I felt proud to be asked and during the meeting, I suggested a glass art program be established to complement the scientific glass program.

The following month Dr. Contini called to ask if I would teach a glass art course in the evening as an adjunct faculty member. After talking it over with my wife Pat, I enthusiastically accepted the offer. This began 20 years of teaching and advising under three gifted and dynamic Presidents, Dr. Contini, Professor Joan Baillie, and current president Dr. Michael Gorman. These three dedicated and highly talented educators impacted the College in ways that elevated the Glass Education Center onto the international glass landscape. As a full-time studio artist, I felt privileged to share my glass experience with the students and to witness the professional focus on helping students reach their full potential. As a student I was totally unaware of the thought, planning, and preparation the students are the recipient of.

Because of my experience and stature as a professional studio artist/craftsperson, on occasion I was invited to participate in some of the meetings focused on glass art education. I came to see the educators as holy people dealing with a level of complexity and consequence of decision making that impact the student’s best interest.

The Glass program is a remarkable study in advancing and building on a collective vision. One very visible indicator of the program’s success is the fact that it has outgrown it 13,000-square-foot space in Alloway, N.J., 12 miles from the college campus in Carneys Point. President Gorman is adding to the scaffolding his predecessors set in place, by relocating the Glass Education Center to the campus. The new 20,000-square-foot, state-of-the-art facility will honor long-time benefactors Samuel and Jean Jones, and will house the Paul J. Stankard Glass Studio/Lab, scheduled to open in September 2019.

Salem’s Glass Programs’ Future: A 20,000-square-foot facility

The glass program currently has upward of 160 students enrolled, and with the new facility, learning opportunities will be enhanced by new equipment, a heightened sense of school spirit, and the proximity to the classrooms, student center, and the library, which houses the Contemporary Glass Resource Center.

The Samuel H. and Jean Jones Glass Education Center will be a facility like few or none elsewhere in the world. This world-class educational space will double the number of flameworking stations with glass lathes in a well-lit and ventilated space. It will allocate generous space to the furnace-working area for hot glass blowing and casting, expand the area for fusing and kiln-casting, and improve the cold-working area for glass cutting and polishing. There will also be an area for welding and fabricating metal armatures for large-scale sculpture. In addition, there will be a new 280- square-foot gallery for student and professional exhibitions.

Salem's students have an opportunity to study and experience excellence through the school's exceptional permanent collections of scientific glass and glass art. The thoughtfully curated collection is a visual celebration that challenges students to take pride in knowing that their skills will eventually lead them to this level of accomplishment.

A factor that also makes the Samuel and Jean Jones Glass Education Center so attractive to the school is that it expands opportunities for the student body to take glass courses as electives.

I left working as a scientific glassblower in 1972 to be on my own as a self-employed studio artist crafting floral paperweights and small-scale sculpture. Looking back, it was a gutsy thing to do, even with Pat's encouragement. Our 4th child had just been born and it took time to push past the worry of providing for my family. Prior to being totally on my own, I had been working part-time nights and weekends with encouraging success. With long hours and a few positive-thinking books, I felt blessed being a self-employed artist.

Thank you, Salem

In the early 1980s, my income rose substantially, based on collectors' appreciation for my artistic point of view. In 1984 Pat and I decided to buy a new Cadillac – an important emotional symbol for me because I had spent many years driving junkers that demanded constant repair.

The Salem experience was never far from my mind, and when we picked up the new car, I told Pat I wanted to take her for a ride. The destination would be a surprise.

When I turned onto Hollywood Avenue in Carneys Point a half-hour later, Pat recognized that the road led to Salem Community College and she immediately understood the meaning of the trip.

I circled the wrap-around driveway, turned and drove home. While I had always been grateful that the Salem glass program had given me the skill to earn my living, this had been my first visit back in 23 years.

In the past half-century, both Salem Community College and I have evolved. The techniques and hand-skills taught me at Salem lent themselves to my building on an art form that flourished in Europe in the mid-1800s. As I was growing with artistic maturity, I was challenged to build on the European paperweight tradition by infusing the art form with an American voice inspired by, among other factors, the poetry of Walt Whitman.

My floral glass art has attracted interest among collectors and museums around the world, and I would eventually receive two honorary doctorates, and an honorary associate's degree in glass art from Salem Community College. I enjoy lecturing and demonstrating at glass-centric cultural centers and museums with collections of contemporary glass art. My glass floral designs are represented in more than seventy-five museums worldwide. But my educational legacy has been teaching young students in the Salem glass program and eventually assuming the role of the artist in residence.

Now that I am only 75, I'm receiving "old-man" awards (my term for lifetime achievement recognitions). The 2018 Distinguished Alumnus Award from the New Jersey Council of County Colleges represents my commitment to excellence and self-directed learning; while I have always had difficulty reading, I have immersed myself for more than 40 years listening to audiobooks focused mostly on the classics.

And occasionally, I think of my father, who passed away in 1976, who experienced my budding success and was very proud of me.

Paul J. Stankard Studio Lab, the largest of any academic institution, allows for instruction of both scientific and creating flameworking at both the bench and on the lathe.

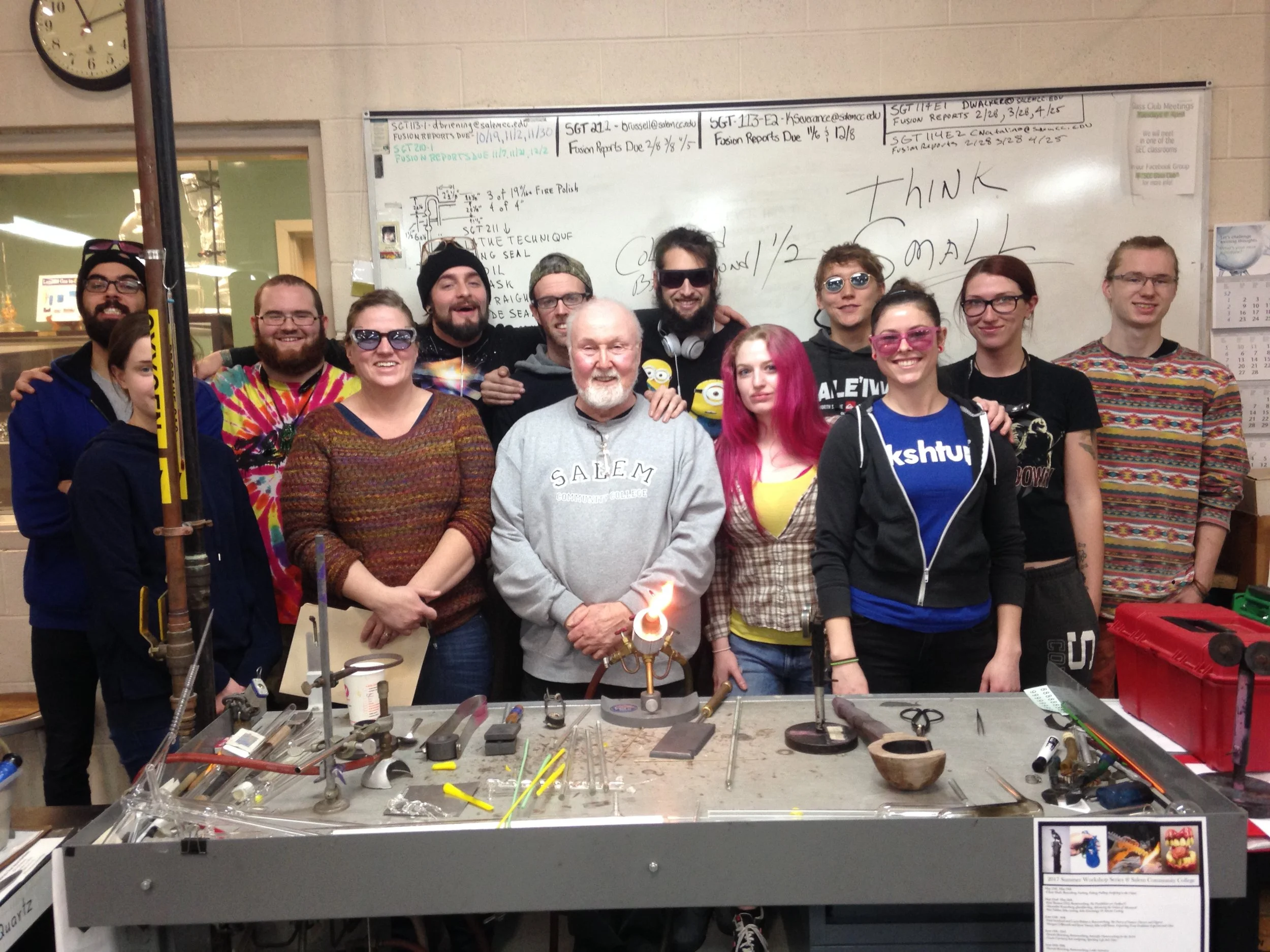

Artist in Residence Paul Stankard posing with students at the SCC Glass Education center after demonstrating glass encapsulation at the torch.

The hot shop is just one of four glass studio areas housed in the Paul J. Stankard Studio Lab; the studio also includes a flame shop, kiln shop, and cold shop covering all areas of studio glass.

Instructor Alexander Rosenberg demonstrating how to create a glass cylinder in the hot shop.

Scientific Glass Technology students develop a solid understanding of scientific glassblowing so they are able to fabricate apparatus according to technical specifications.

Instructor Dennis Briening demonstrating to the students on the lathe.

Honeybee Swarming a Floral Hive Cluster, 2010, D. 8.0 inches

Golden Orb Floral Triptych, 2009, H. 5.37 x L. 7.75 x W. 4.0 inches; From the Minkoff Collection

Millville Rose Paperweight