My Healing Journey

My Healing Journey:

The Art, Science, and Spirituality of Curing Prostate Cancer

I have a beautiful career. I am a 71-year-old studio glass artist whose work has attracted an international audience and has been included in collections in more than 60 museums around the world. Throughout the past four decades, my work has grown and reflects my emotional and artistic maturity. Up until a year ago, my whole life was glass – my working life, my social life, my quest for beauty. As a glass artist, I was obsessed with discovering beauty and humanity from behind a 2,300-degree flame while sculpting hot glass.

But then I discovered an unknown dimension of my personality on my journey through prostate cancer. I connected to inner strengths, a heightened spirituality that brought out positive attitudes that I shared with my wife Patricia throughout my treatment. When I look back over a three-year period that encompassed diagnosis, treatment, and radiation therapy, what comes into focus is the beauty and humanity of the people and an institution that worked to extend my life. I not just saw, but experienced, how Pat and I, over 50 years of marriage, have fused together emotionally and approach such challenges as one. I also learned how saintly people can be – and how precious the gift of life is when you are dealing with life-challenging medical issues.

This book tells that story – of how beauty can be discovered in unlikely places, and how I have experienced a heightened spiritual maturity, nurtured by the saintly people who, like the Holy People of the Bible, healed by the laying on of hands.

This book is a blend of personal experiences with informative sections written in everyday language by top medical experts. Through it, I share encouraging information about the successful treatment of prostate cancer.

It was encouraging to learn that most prostate cancer conditions are treatable, and that the process was doable and well within my emotional tolerance level – meaning, within the tolerance level of every man. I also want the families of the loved ones affected by prostate cancer to gain an appreciation of what occurs throughout the healing process.

I am not a doctor or a scientist. I have been blessed by the treatment I have received from some of the top people in the field, which is why I have invited them to overlay my humanistic narrative with information about the most recent breakthroughs and techniques in the treatment of prostate cancer.

This book shares a journey that my wife Pat and I began three years ago, when some numbers in a blood test were ominous. The story continues through a biopsy that showed cancer of the prostate, to the present – having concluded my radiation treatment.

I am not particularly courageous when it comes to medical treatment. This has been, by far, the most serious medical situation I have ever encountered. If I can get through this, any man can.

***

Dr. Robert B. Den

Radiation Oncologist

Thomas Jefferson University Hospital

I’ve always been an early riser, and my routine is basically the same today, with one exception that’s been brought on by my treatment: I have drastically reduced my coffee intake.

This change in my routine provides me peace of mind in preparation for my radiation treatment. I have diminished control over when I urinate or have a bowel movement, and encounter a frequent – and constant – sense of urgency to avoid an accident. The situation has become more acute when waiting for my treatment because the oncologist wants a full bladder. When my bladder is full, it balls up and changes its position in the body and clears the path to give the radiation beam a direct hit to the prostate.

I had 39 radiation treatments, Monday through Friday, spanning eight weeks.

Over the weeks, my anxiety levels diminished and eventually evaporated. My view of the treatment changed from apprehension to a sincere appreciation for the beautiful people who were leading me through the healing process. I think of them as Holy People. They dedicate their lives to healing the sick.

Here is why I’m sharing my experiences: For the last 20 years, in addition to sculpting hot glass, I’ve written poetry, essays, articles, and two books – mostly relating to studio glass art. Over these years, I’ve detailed the challenges associated with artistic growth, as well as the value of self-directed learning. With my need to write and share, the challenge of dealing with my prostate cancer is now dominating my psyche. I find it strange that I now give little thought to my career as a glass artist. I’m directing my energies to writing about my fears and joys relating to my cancer, and the reality of Death, and how God’s spiritual realm dominates my thoughts.

I’ve written this narrative because sharing my experiences may benefit others. I’m also writing about my experiences because I’m a writer, and this process benefits me. By sharing, an artist grows, and that holds true regardless of how and what you are expressing.

This is the story of my diagnosis and treatment, and how I came to give my total emotional and intellectual trust and respect to the people of Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Pat and I have strengthened the trust with which we regard our doctors, nurses, therapists, and support staff. I also wanted to write about how overcoming cancer is a spiritual state of mind, much like my spiritual attitude toward art-making. Throughout my career as an artist, I’ve embraced the motto of the Benedictine monks: To Labor is to Pray. This attitude, and this account of my prostate cancer treatment, is offered up as a prayer.

I’ll start at the beginning. Over a two-year period, a blood test that indicates possible prostate problems showed elevated numbers. The bloodwork, which was routine for a man my age, was ordered by our family physician, Tara Tomasso, M.D. Her dedication and experienced judgment on a variety of family medical issues – but specifically my bloodwork numbers – has been a blessing. She suggested I see a urologist for further testing.

I made an appointment with Karl H. Ebert, M.D., of the Delaware Valley Urology group. Pat and I went to Dr. Ebert’s office and, after several appointments and a number of tests, culminating with a biopsy, I was diagnosed with an early stage of prostate cancer.

When I look back and remember my first biopsy, I recall being afraid and having considerable anxiety. The idea that a serious medical procedure would originate through my anus petrified me. When I was lamenting about the procedure to my brother Robert, he said, “Be thankful your prostate gland is less than 2 inches from your opening.” And little did I know that the needle biopsy would be made more comfortable by having my prostate gland numbed by Novocaine.

When I look back, I realize my worrying was worse then the procedure. But what I did find eerie about the biopsy was the series of sounds and sensations: the cocking sound of the gun used to shoot a needle into the prostate to extract samples, the impact of the needle, and the click of metal hitting a glass petri dish as 12 samples were ejected in the dish. I was numbed by the anesthetic, but my ears were at full alert to what was happening. The aural experience was on a par with scraping fingernails across the blackboard.

The result of the biopsy showed early-stage prostate cancer. I was afraid and not sure or confident about what to do. I called my friend Anthony J. DiMarino, Jr., MD, who is a professor of gastroenterology and hepatology at Jefferson and practices at the hospital, about my diagnosis. He suggested I go to Jefferson for a second opinion, which I did.

It was kind of him to make an appointment for me to see a doctor named Leonard G. Gomella, M.D. Coincidentally, a few days before the appointment, I was at the barber shop waiting my turn, and reached for a copy of Philadelphia Magazine with the coverline “Top Docs.” I flipped through the article and saw the name Leonard G. Gomella, M.D.; he was identified as chair and professor of the Department of Urology at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital. The article featured him as the top urologist in the Philadelphia area.

I actually chuckled out loud, thinking what a beautiful GMC – “God-Manufactured Coincidence” – this was, because I would be seeing him in a few days.

Pat and I drove to Jefferson Hospital with a map showing the buildings, recommended parking, and hospital campus identifying the location of Dr. Gomella’s office. This information was provided to us through the mail soon after the appointment was made. Closer to the date of the appointment, I received a follow-up phone call.

Before the first appointment with Dr. Gomella, we felt that our treatment was in progress through the mail and phone contacts. We received several packets of information. As a dyslexic, I didn’t even try to wade through them. I relied on Pat, the analytical one in the family, to digest these details. Jefferson’s proactive approach was much appreciated and alleviated our initial anxiety.

Armed with our map, we set off for our first appointment on Monday, Feb. 6, 2011, at 11 a.m. We kiddingly referred to ourselves as two country folks having a “big adventure in the city.” I drove up to the seventh level of the garage, the top, which was open and sunny, offering an unusual and interesting view of the area’s skyline and rooftops. It was an easy walk to 833 Chestnut Street, a majestic, century-old, but meticulously maintained building.

We sat in the waiting room. It was huge – certainly the largest I had ever experienced. There were probably 50 seats. When we entered, I signed in on a computer – also a first for me. A flat-screen monitor flashed pictures and biographical information about the urologists, presenting them in something of a celebrity aura. The size and technological sophistication of the waiting room reinforced the contrast between my previous experiences with medical practitioners, as opposed to innovators in the field of medicine. It made me aware that I was seeking help from the big-leaguers.

While we waited, Pat filled out lengthy questionnaires relating my prostate issues. After about ten minutes, a nurse came into the waiting room and called my name. She led us to the inner sanctum – a ten-by-ten-foot examining room.

Within a short time, a young doctor in his early 30s, followed by two students, entered the room. He introduced himself as Dr. Gomella’s resident. He began the preliminary interview and reviewed my vital signs. He then asked to perform a rectal examination to feel for abnormalities in my prostate. I used to dread this procedure; now I’m confronting the reality of my situation. Over the last 20 years, this exam had always been difficult for me. In fact, often throughout my fifties, I would pass on having it done, much to the disapproval of my family doctor. But once I was diagnosed with prostate cancer, I submitted to a rectal exam without hesitation.

The resident performed the easiest exam I had ever experienced. As I assumed the position, he held his lubricated gloved finger against my sphincter muscle and then inserted the finger into my anus. As I pulled up my pants, I told him that this was the least uncomfortable prostate exam I remember having. He then said – talking both to me and to the two students behind him – that holding the finger on the sphincter for three or four seconds allows the muscle to relax and offers less resistance.

I was a little self-conscious about sharing this publicly – until recently, when I learned that eight buses in the SEPTA system in Philadelphia are now traveling throughout the city with an advertisement proclaiming:

DON’T FEAR THE FINGER

I later Googled “Don’t Fear the Finger” and learned that it’s the slogan for an advertising campaign organized by the Pennsylvania Prostate Cancer Coalition.

***

I value my dear wife Pat’s counsel and that she is by my side every step of the way. I now understand why most patients who are dealing with serious illnesses – in my case, cancer – have loved ones accompanying them.

Shortly after the preliminary interview and exam by the resident, Pat and I met Dr. Gomella. We were impressed with his easygoing personality and his air of gentle authority. Dr. Gomella, who appears to be in his early-60s, is respected worldwide for his innovative contributions in urology, most notably for designing and implementing a unique and now widely accepted multidiscipline approach toward treating cancer.

After he looked at the information I had had transferred from the office of Dr. Ebert, my first urologist, Dr. Gomella ordered my second biopsy to verify the results and establish his baseline for gauging his treatment strategy.

A month later, after Dr. Gomella had received the result of the biopsy, Pat and I returned to his office. Dr. Gomella confirmed that I had prostate cancer in the early stages. Cancer is serious, but in my case, the prognosis was very good, because my cancer had been detected early.

We asked many questions, mostly emotionally charged and not technical in nature. I asked, for example, “Can I give cancer to my wife while being intimate?” With a warm smile, he said no. Throughout our conversation, he addressed our concerns in a layperson’s vocabulary, showing no hurry to move on, focusing his full attention on our situation – something that meant a great deal to us.

But near the end of the interview, before we made the decision to wait and watch the speed of the progression of the prostate cancer rather than immediately embarking on aggressive treatment, I had to ask the tough question. I felt timid asking, but I needed to hear the answer to reinforce our emotional state of minds.

“Dr. Gomella,” I asked, “is this going to put me in the ground?”

He regarded me thoughtfully for a second and gave me a lighthearted response.

“No,” he said. “I don’t think so. In fact, you could be the poster boy for having prostate cancer in its earliest stages.”

Throughout my experience, I became increasingly aware of the hospital’s culture of genuine respect and empathy. It gradually disarmed my anxiety, and I realized I was being cared for by special people who are dedicated to enhancing the dignity of life in general – and my life in particular. Dr. Gomella, after learning of my preference for what is called “watchful waiting,” told me that we would monitor the prostate with blood tests every six months and a yearly biopsy. We left the Urology Department feeling encouraged by the added knowledge and reassurance from Dr. Gomella’s poster-boy analogy.

***

Before the third biopsy, I optimistically believed my slow-growing prostate cancer, left alone and monitored by watchful waiting, would allow me a full life – easily matching my mom and grandpa's active 88-year life spans. But the third biopsy, 15 months later, showed the cancer had grown: I was no longer in the “early” stages. I was now a member of the “intermediate” category, and lost my poster-boy status.

On this third visit with Dr. Gomella, he reviewed the results of the tests with us. I would find out much more detail later, but in this meeting, he briefly outlined three options to consider in the treatment of my prostate cancer.

“Watchful waiting” was no longer appropriate. I was not entirely displeased by this, because I came to dread the thought of a yearly biopsy, and had entertained the idea of requesting that the prostate gland be surgically removed.

Dr. Gomella concluded the meeting by telling me he wanted to bring an oncologist into the treatment strategy sessions. When I realized my case was being discussed as an educational study for the medical students, I felt fortunate. After having a variety of doctors interview me, it was a blessing to be the recipient of Dr. Gomella’s pioneering techniques involving collaboration and synchronized team consultation.

As an example of that, I was told by one doctor that I would most likely have hormone treatments. When I asked Dr. Gomella about this, he said, “We collectively discussed it, and decided it wasn’t called for.”

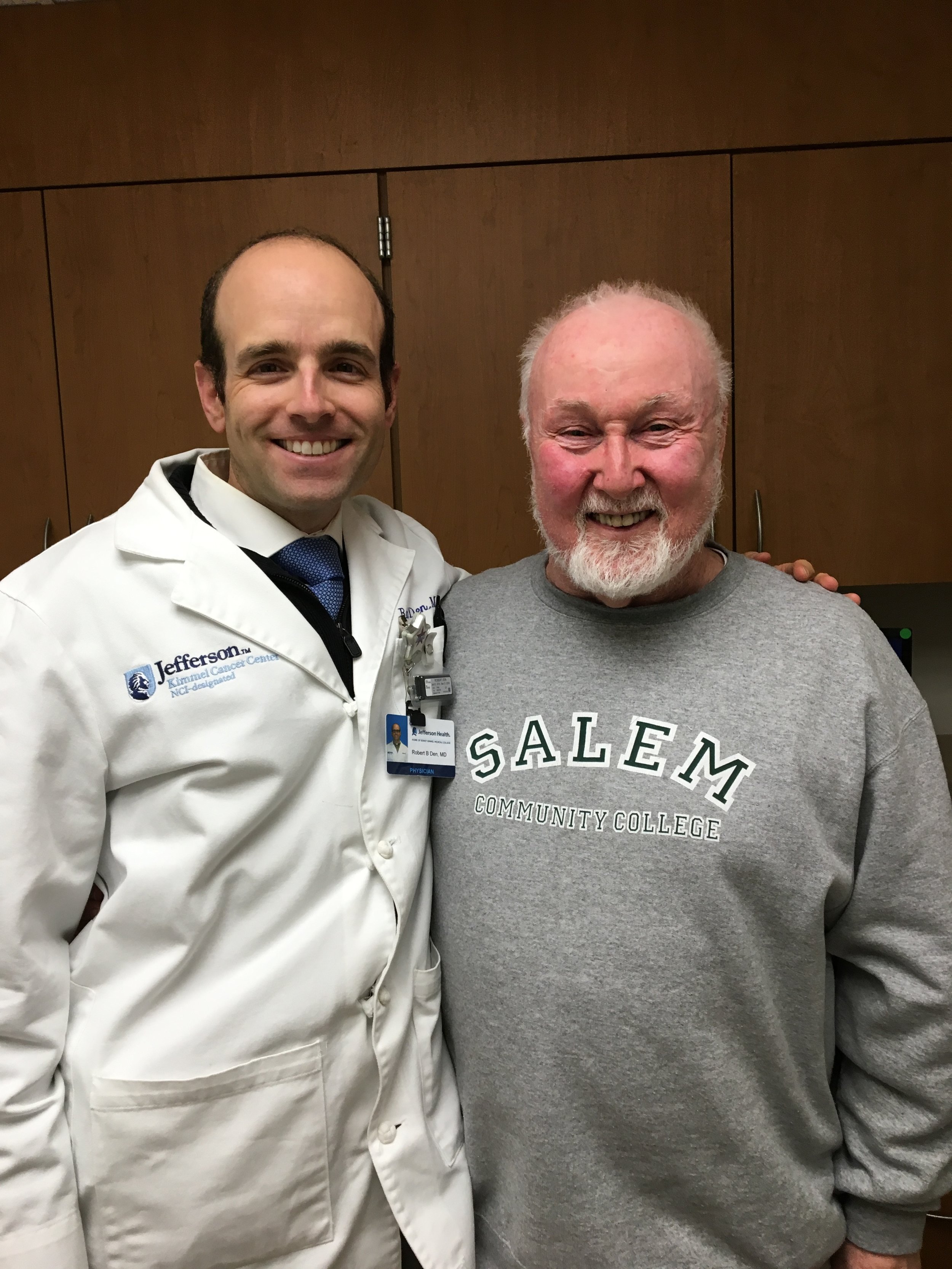

Who comprised the “we”? Among them was Dr. Robert Den, an assistant professor and co-director of the Multidisciplinary Genitourinary Oncology Center. I would come under his care three months later in the process, after the third biopsy, when the Bodine Cancer Treatment Center became my home base. He is a youthful, 40-ish Harvard grad with an easy smile. In addition to healing people and teaching, Dr. Den is researching techniques to deliver treatment that advances effectiveness with the least possible discomfort and side effects.

One of the first things that impressed me about Dr. Den was that he wore a yarmulke. A yarmulke is a small cap that, in the Jewish faith, signifies a respect for God above us. It was a sign to me that he is a spiritual man and I appreciated that. In the reality of my cancer and in the environment of the treatment center, my spirituality has been heightened. Throughout my life as a practicing Catholic, I have celebrated the spiritual, and now my religious beliefs have been enhanced by this serious medical challenge.

***

There were two locations for my visits at Jefferson: the building where I had first seen Dr. Gomella, and the Bodine Center for Cancer Treatment, two blocks away. Our third meeting with Dr. Gomella took place at Bodine, the first time he’d met with me there. It signified the move to a new home base for the location of my treatment.

The meeting at Bodine opened up a wider range of considerations. Dr. Gomella explained the three options available for my treatment – surgery, seeds, and radiation.

Surgery would involve the complete removal of the prostate. I had talked to several people about this, and got the impression that it could interfere with bodily functions down the road. Seeds – the implantation of upward of 100 small radioactive rods, for some reason did not appeal to me. Radiation therapy would involve killing the cancer cells with a concentrated beam of electromagnetic energy.

Pat and I decided on the spot. We looked at each other.

“I kind of like radiation therapy,” I told Pat.

Pat smiled and said, “I think that’s a good choice.”

I turned to Dr. Gomella. “Let’s go with the radiation.”

His response: “That’s what I would do. It’s the least invasive.”

A Collective Decision

Our collective decision was relayed to Dr. Den, who endorsed our judgment and then – being an oncologist specializing in treatment and research about radiation therapy – initiated a plan of attack. He ordered two tests and two procedures that prepared me for eight weeks of radiation.

Dr. Gomella told me he would be back on my case soon after I finished the radiation treatment. So now, officially, I was under Dr. Den’s care.

He arranged for an MRI and a CAT scan, tests that visualized the inside of my body and gave him an indication of the degree of the cancer. Dr. Den also ordered the insertion of “fiducial” gold markers. The word fiducial means something done for reference to determine a location. Combined with external tattoos, the markers give the therapists pinpoint precision in the radiation treatment.

The MRI was a challenge. Standing in my stylish cotton gown, I was helped onto the plastic table that would glide me into the heart of this large technological marvel. It was to be a 45-minute procedure, and I was apprehensive about my ability to withstand this confinement.

Even with ear plugs provided by the therapists, I was surprised at how loud the various thumping and pulsating noises were. I distracted myself by imagining I was a 71-year-old hipster and the thumping was rap music. That fantasy didn’t last long, so I focused on my daily prayers for a short time, and then came back to earth and mentally planned a lecture and hot-glass demonstration for that fall at Salem Community College in Southern New Jersey.

I was surprised – and, in fact, pleased – to discover my disciplined level of focus in this claustrophobic environment. (At one point, I opened my eyes and was startled to note that I was only about three inches from the inside surface of the tube.) I had to work hard to overcome what was for me a frightening reality that reinforced the claustrophobia I was experiencing. I shut my eyes immediately and kept them closed for the duration of the procedure. I focused on visualizing myself in front of a group of enthusiastic students sharing my glass art experiences – an activity I love. Once I transported myself into the mental zone of teaching, the state of concentration allowed me to become oblivious to my surroundings.

This marked another milestone in my life’s journey: I had never before gone inward to the exclusion of the outside world. This was the first time I focused and escaped from this level of emotional discomfort over such a length of time, and successfully blocked out the distractions, creating an internal universe that was surprisingly blissful.

With the MRI images finished and my head pounding, Pat and I rushed three blocks to the Bodine Center for a CAT scan that was scheduled to start within a half an hour. Following the CAT scan, I would then have three tattoos, one centered approximately three inches above my penis and the two others on the same plane on both hips. These markers allow therapists to line up the radiation beam directed at my prostate.

The CAT scan would have been a piece of cake but for one exception: the fact that I had to drink four glasses of water to fill my bladder. After the second glass, I worried incessantly I wouldn’t be able to hold it. While lying on the bed of the medical apparatus, I imagined the worst case scenario: losing control of my bladder and having an accident. I envisioned grabbing and bundling the sheet covering me and peeing in it to lessen my cleanup and then somehow dealing with the embarrassment. I made it, but not by much; after the test, the therapist – sensing my urgency – immediately led me to a nearby men’s room. This was the first time I realized how much emotional and physical stress come with not being able to control one’s bladder.

The concern about drinking four glasses of water foretold a new set of challenges that I never could have imagined, and would work to overcome.

Immediately after the CAT scan, I was tattooed, based on the information recorded during the scan. The CAT therapist (one of the many Holy People I would encounter) started tattooing three dots and then drawing three circles to enclose them with an ink marker on my torso. I wound up with the dot tattoos encircled with hand-drawn geometric symbols applied with a special ink. To me, it looked like I had been branded, like a steer in an old cowboy movie.

Pat and I came back a week later for metalwork –gold-leaf markers implanted in three locations in the prostate to define the parameters of the gland, so the radiation therapy could be accurately focused. Insertion of the gold markers was a minor variation of a biopsy, but involving the same level of discomfort. But I had the consolation of Pat giving me a new nickname: Golden Boy.

While no one would argue that the procedure was easy or pleasant, I can say in hindsight that I was proud to go through the various tests with cheerfulness. This was important to me. If I approach the challenge with optimism and with a celebratory nature, I’m able to dilute tension that could erode my confidence. In all honesty, I do this because I know that I have to fight the tendency to avoid a pity party by saying, “Oh, shit, I don’t need this. Why me?”

It was at this point that I realized how doable and manageable the process is. I don’t think of myself as a strong, “give-me-your-best shot” type of a person. At the same time, I had become aware of how much easier and more effective this treatment was today compared to even a few years past. I realized how fortunate I am to be living at a time when this technology is available.

Men can get through this. If I can do it, any other man can do it, too.

***

When describing a typical day of treatment, I’ll start at bedtime the night before. My routine, established over 40 years of working at home, has been completely disrupted. From sleep to commuting to bodily functions, everything has been flipped. Other than interacting with Pat and family and going to the gym three to four days a week at 6:00 a.m., very little of my daily routine is the same.

These days, I’m generally in bed shortly after 9 p.m. and expecting a night of uncharted territory. I’ve been waking up one or two times between 12 a.m. and 2 a.m. with a major urge to urinate, getting rid of as little as 2 ounces up to a recent record of 5 ounces and any amount in between. At times, I’m standing over the toilet bowl dribbling my way toward relief. It’s hard to go back to sleep, so I end up writing on the computer for a half-hour or so before urinating again and going back to bed, as I pray for additional sleep.

About 30 days into my 39-day radiation treatment program, I learned to deal with the irregularities of my bodily functions and occasional fatigue throughout the treatment. During my second scheduled mid-week office visit with Dr. Den (Pat accompanied me for every Wednesday therapy and appointment visit), I told him that my major challenge at that moment was dealing with the frequency of urinating along with frequent bowel movements. He wasn’t surprised; he told me that my reaction was not uncommon and that radiation affects people in many different ways.

Dr. Den prescribed Tamsulosin to improve my urinating performance, noting that he might increase the dosage as the treatment progresses. He also advised me to take the over-the-counter drug Imodium to counter my diarrhea.

But it was my dear wife Pat’s wisdom that produced perhaps the most immediate peace of mind. She suggested we go to the local medical-supply store to select a few products for dealing with incontinence: diapers, pads, and a specially designed bottle for urinating that I keep in the car.

The first day wearing a diaper, I felt reassured even though it wasn’t needed. That evening, before taking my shower, I was curious about the effectiveness of the diaper and urinated in it as a trial run. To my surprise, the padded material absorbed the urine and the elastic band kept my clothes completely dry. I was happy to know I had more freedom with less worry.

My approach to the diaper test paralleled my curiosity and method as an artist. When something doesn’t work at the bench, I start anew and keep searching for the best results. Just as I often feel when a work turns out well, I was elated to discover that the diapers had merit.

Before starting treatment, I planned to work in the studio after my mid-day nap. But to my surprise, I’ve lost my discipline to work in glass. I recently told a visiting group of students that I lost my “mojo” because of fatigue. It’s complicated, because I’m proud of my professional accomplishments and have been happiest working in my studio. That’s why I do return to the studio in the afternoons – not to work at the torch, but to think about my future artwork, meditate, and write the words you’re reading now. I have a new mindset. I am focused on healing and meditating on the bittersweet reality that I will die.

Let me clarify what I just wrote: At age 71, this illness could have ended my life – as could a virtually limitless number of other afflictions. Right now, thanks to current medical technology, what would have ended my grandfather’s life, and possibly my father’s, has become manageable. I have a good prognosis.

Still, I’m well aware that I will die, if not from prostate cancer, then from any number of causes that I hope will allow me to die peacefully after having a long and healthy life.

***

I often wake up before 4:00 a.m. but don’t like to get out of bed earlier. When I leave the house, my routine is to go to the convenience store for coffee and a toasted bagel. Early in my treatment, I gave up coffee for a few weeks (it is a diuretic and, with the urinary challenges stemming from my prostate, that was the last thing I needed), but a lifetime of enjoying coffee trumped the peeing issue. When I drive back and park in my driveway between my home and the studio building next door, I sit in the car eating the bagel and drinking coffee while I listen to an audiobook downloaded to my iPhone.

After the coffee and listening for 20 minutes, I walk to the comfort of the studio, and enjoy saying my daily prayers and meditating in the serenity of the early morning. I’ve meditated on the same prayers throughout my adult life and now, with my computerized text-to-speech program, I’ve added a heightened dimension to my devotion. The program allows the repetitive chanting of the “Jesus Prayer,” said by Christian mystics and especially practiced in the Eastern Orthodox faith. I open my morning prayers by contemplating five minutes of chants followed by the Our Father, the Hail Mary, a novena to Saint Joseph, a petition to Saint Jude, and more chants to conclude. The entire devotion generally takes 20 minutes, and is a strong source of emotional strength that prepares me for what’s ahead.

During my radiation treatment, I continued going to the gym and leave the studio around 6 a.m. Two of the sessions are with a personal trainer, and the other two mornings, I’ll swim laps. When I’m training, I warm up before the 6:30 session. I noticed that I was slowly getting weaker over the course of my radiation treatments. I’d like to think that, if I’m lifting or pushing the weights to my maximum strength, regardless of the amount of weight, there is a health benefit.

After my exercise, I’m back home at 7:20 to begin preparation for the day. With time to spare, Pat and I generally talk about family, upcoming commitments like Thanksgiving, and the usual funny banter that stems from 50 years of marriage. I watch the time and usually leave the house a little before 8:00 a.m. for my Monday through Friday trek to Thomas Jefferson University Hospital.

Before this journey began, it had been a long time since I had commuted in rush hour traffic to Center City Philadelphia by way of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. This has reminded me of how fortunate I’ve been to work at home since 1972, in a comfortable environment with no commute. I was pleasantly surprised, after checking the odometer, to learn it’s only 15.6 miles from my house to the seventh level of the parking garage, a trip that generally takes 35 to 40 minutes. Traveling south across town on 8th Street to the garage at 10th and Chestnut, I notice the hundreds of people bustling to work. I’ve often thought how interesting it would be to live in Center City, with all the conveniences within walking distance.

I arrive at the garage, and wind up on the top floor, even though there are openings below, because I enjoy waiting on the empty level in the sunny open air. I park the car in the same spot and listen to TED Talks (lectures on all aspects of the advance of human achievement) or National Public Radio while waiting for 8:50 a.m.

At the Bodine Center around 9:00 a.m., I take the elevator down to the Radiation Treatment area and, as the elevator door opens, I’m facing Nicole, who’s the senior patient registrar. She’s a youthful woman in her mid-30s from South Philly and has an attractive smile – a smile that in itself feels therapeutic at the start of a new day of treatments.

The routine is to check in by swiping my identity card’s barcode under a scanner, along with validating my parking card. When I scan in, the computerized system also notifies the radiation therapists – in my case, the D unit or the Holy People of the D-team, as I call them. Because of my urinary challenges, Nicole, who is in touch with the radiation units, notifies me to start drinking three glasses of water approximately 15 minutes before the treatment to fill my bladder and protect it from a term I probably invented: radiation “splash.”

I take a locker key from the wall and go change. In the locker room, I’m changing into two gowns for front and back coverage. Generally two or three men are dressing or undressing at the same time and the casual conversation centers on types of cancer and the number of treatments left. Prostate cancer, in my observation, seems to be the most common cancer treated next to colon and anal. Prostate, colon, and anal cancer require changing into a gown. I’ve benefited from the esoteric information being shared about the challenges – such as urine-absorbing pads, external catheters (a.k.a., condom catheters), diapers, and the best style of underwear to accommodate the added protection. It’s amazing how effective this big brother network can be.

From the locker room to the waiting room, you feel a spiritual kinship or camaraderie that is nurtured by seeing the same people over the course of weeks and, in some cases, months. It seems to be an equal number of women versus man being treated and, judging by the conversations, prostate cancer is on a par with breast cancer as the two largest categories.

Nicole not only greets patients and records their arrival, but also organizes the flow of patients to the four radiation therapy units. She protects the seamless and no-stress nature of the experience in the two waiting rooms.

The staff I come into contact with call me Mr. Stankard. However, because I deal with Nicole Monday through Friday, and feel appreciative of her help, I asked her to drop the “Mister” and call me Paul.

“OK, Mr. Paul,” was her response. So now I am Mr. Paul.

This culture of respect exemplifies the entire Bodine Center, and is felt the moment you pass through the revolving door at the corner of Sansom and 11th Street.

The hospital is expansive and takes up three or four city blocks. I recently discovered, during inclement weather, that there is a route from the parking garage to the Bodine Center that is enclosed. I can walk a city block inside an atrium-type environment. When I’m inside, it seems as though I’m in a cocoon, enveloped in healing. But when I leave through the front door and take the street route, I come back to reality – it’s cold, people are rushing by on the sidewalk, horns are honking, a young homeless man is a fixture, and business people are marching in their suits and ties, armed with their briefcases.

I never imagined that a hospital could be so noble and life-affirming, and I’m astonished at how important the environment that nurtures a sense of well-being is to the healing process.

Experiencing the healing virtues of Jefferson has made me appreciate the state-of-the-art science that not only underpins my healing but has become a resource for the Delaware Valley. In truth, though, my mental response to this journey has been emotional. I am no judge of science, but I am able to gauge kindness, caring, and culture. I am proud and grateful for the scientific advances, medical research, and scholarship directed toward my treatment and that of patients in the future, but I am most attuned to the hands-on people working at the facility.

This atmosphere, I suspect, is made possible by a collective mindset that is a daily challenge to maintain. Such a culture does not just happen. It’s a result of attention to detail … and, in my case, the detail is me.

The culture at Jefferson empowers the doctors, nurses, therapists, and support staff to work in unison, reinforcing focused ideals on the individual cases. From my emotional standpoint, it boils down to this: I’m not the only patient there, but I am made to feel that I am the focal point of their collective wisdom.

When I review the three years that I’ve been treated at Jefferson, one of the biggest challenges for me was summoning the discipline needed to complete the eight weeks of radiation treatment. Eight weeks of treatment essentially became a full-time job. It was not the most intense aspect of my treatment, but it demanded my full attention Monday through Friday. In fact, the “job” made me appreciate the weekends. The sense of freedom and relaxation offered by a weekend was akin to summer vacation when I was a kid.

Let me provide some more details on the treatment routine. I was assigned to the 9:30 a.m. slot. – the head of the radiation department accommodated my desire to continue my early-morning workouts, another example of the caring approach of this team.

Before the treatment, I would be in the smaller of the two waiting rooms. The small room was conducive to friendly conversation. It opened to the hallway that led to the radiation machines, creating a feeling like the on-deck circle where the next batter waits to step up to the plate.

The analogy continues: I am called up by a loudspeaker, and I proceed to the D Machine, one of four multimillion-dollar radiation units.

During my first few visits, I was very tense, but, as the treatment continued, I became more comfortable with the procedure, and especially with the therapists, the Holy People of the D team.

In one of my earlier Facebook posts, I referred to lying on the plastic plank that slides me into what I called “the throat of the monster.”

I told Dan, one of the three therapists, about that post.

He looked at me with a stern expression, and pointed to the machine.

“That monster,” he said, “is saving your life.”

I was startled by how truthful that was, and underwent a major attitude adjustment at that very moment.

***

There is something very special about seeing the same eight to 12 familiar faces in the waiting room day after day. It’s a pleasant source of comfort. Near the end of my treatment schedule, I couldn’t stop thinking about and smiling at a comment made by Steve, a 60ish man with a reserved demeanor. He said, “This waiting room is like a party, and everybody has already had at least two beers.”

I haven’t encountered anything close to conceited people – among patients or staff – in the cancer treatment center. I’m sure there are the usual number people with quirks and foibles, but in this environment, I sense only their saintliness.

On the day before Thanksgiving, I looked forward to a beautiful family dinner with my wife, our children’s families, and the grandchildren. There was one more thing to celebrate: That Friday would be my 39th radiation treatment – the final day of therapy for my prostate cancer.

I have been strengthened and comforted by the prayers offered by family, friends, and especially my 5,000 Facebook friends, many of whom read and commented on my weekly chronicles, which evolved into this book.

Black Friday, the day after Thanksgiving, concluded my treatments. This year, I think of it as Holy Friday – the day the last of the golden rays touched my prostate, miraculously healing me.

Holy Friday ended daily treatment and, while I won’t miss the commuting, I will certainly miss the people. The camaraderie among the eight to 12 of us waiting to undergo treatment in my time slot has jelled into an incredible support group. We had a mix of professions, from white collar to blue collar. There were patients from all social statuses, and we sat together drawing support from each other, as if we were monks and nuns in the spiritual sanctuary of the treatment area. This is more than just my intuition: It’s frequently mentioned by the other members of the group being treated.

What we have in common, other than our cancer, is the wisdom we have gained – the realization that life is a precious gift. The experience of cancer and its treatment can be a personality-changer in addition to a life-changer.

In a very strange way, cancer has enriched my life. It’s allowed me to prioritize, and to look inward with clarity and a deeper insight into the depth of my feelings.

What have I learned from this experience? Without wishing to sound trite, I have learned that life is a precious gift. This has made me a better person. In the grand scheme of things, I accept as truth my continuing journey outside of time, as my soul continues the passage.

The End – of the Cancer Journey, and the Beginning of a New One